FIRST THE OIL PUMP BROKE, then the semi’s electronic control unit gave out, leaving Frank Felty and Ronald Woodruff stranded in Clines Corners. Little did they know, they were joining a rather large and unique club: the “broke-down-in-Clines-Corners club.” This is an informal group of travelers whose misfortune has become part of the quirky lore of this iconic roadside stop. Their tales of woe, and perhaps eventual delight, could easily be imagined amongst the John Wayne shot glasses, the glitter globes, and the Route 66 magnets that line the shelves of Clines Corners Travel Center. As a drizzle fell on the high plains, a tow truck was summoned from Albuquerque, some 60 miles west, to rescue their rig.

Felty, resigned to their fate for a few hours, pushed around his Subway breakfast. “I’ve been driving my whole life,” he commented. “What makes a great stop? Food and coffee. That’s about it. Oh, and clean restrooms. This place is good. We’ll kill time eating, drinking coffee, walking around, looking at the jewelry. You know, after a while, you think, ‘My daughter would like that necklace.’”

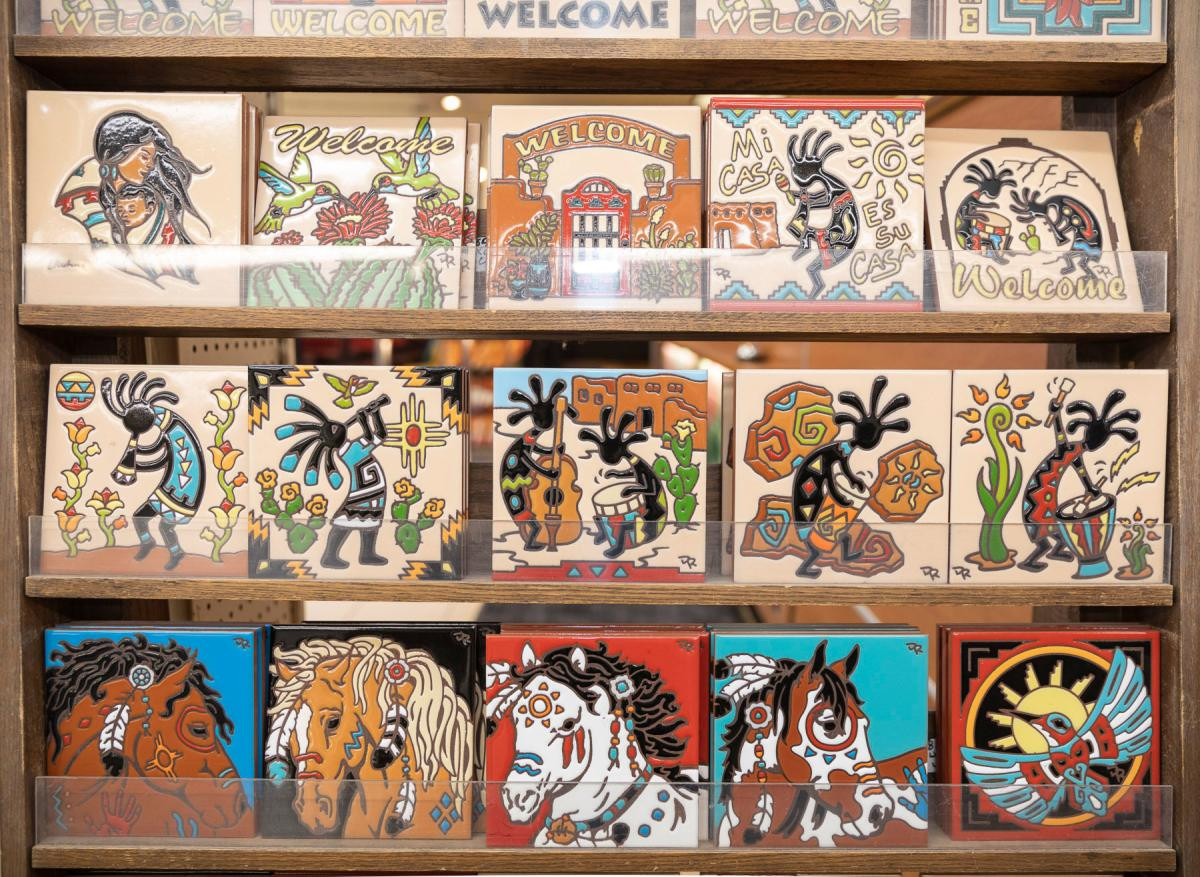

And with that simple observation, Felty perfectly encapsulates the enduring appeal of Clines Corners. It’s more than just a stop on a map; it’s a destination in itself, a curious cabinet of roadside Americana. It’s a gas station, a convenience store, a restaurant, a curio shop, a fudge emporium, a candy store, a rock shop, a jewelry boutique, a post office, an RV park, and surprisingly, a great place to find Ariat boots and Pendleton purses. Let’s not forget the bonus of those clean restrooms and a Zoltar fortune-telling machine, ready to dispense wisdom (or at least amusement). Long before you reach the crossroads of US 285 and I-40, a barrage of billboards herald the myriad treasures within: SPOONS. THIMBLES. ICE. CHILE. KEYCHAINS.

Thimbles? Really?

Yes, thimbles. And so much more. Let’s stop anyway.

Starting in May, Clines Corners is set to expand its already impressive offerings. A full-service truck stop, complete with a laundromat, showers, and five acres of overnight parking, is on the horizon. For those looking to quench their thirst, package liquor sales featuring New Mexico craft beers and spirits will soon be available. And for hungry travelers, La Cocina, a restaurant serving enchiladas and margaritas from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., is poised to become a new favorite. And because what’s a roadside attraction without a little bit of spectacle, fireworks, fireworks, fireworks are also promised.

As both a pioneer and a vestige of the grand roadside stops that once dotted old Route 66 (“Live rattlesnakes!” “Stagecoach rides!”), Clines Corners has been catering to the needs of travelers since 1934. Through four owners, countless New Mexico snowstorms, and an endless supply of “broke-down-in-Clines-Corners” stories, it stands as a testament to roadside resilience. It’s a place that somehow manages to blend the lowbrow with the gourmet, attracting bikers and sophisticates alike. And for those seeking personalized kitsch, the dizzying array of miniature personalized license plates offers a unique souvenir. Just as the author considered a “REBEL” plate, General Manager Jeff Anderson rushed by, a blur of motion on his way to address a ceiling reconstruction issue, part of the ongoing truck-stop expansion project.

“The whole concept here,” Anderson explained in a fleeting moment, “is people stop to use the bathroom, and we get them to spend $20 on rubber snakes and tomahawks. And it works! No marketing book says, ‘Get them to stop for the bathroom and they’ll spend $20,’ but they do. And if they’re hungry, they’ll eat.”

Exterior view of Clines Corners Travel Center on Route 66 in New Mexico, a popular roadside stop for travelers.

Exterior view of Clines Corners Travel Center on Route 66 in New Mexico, a popular roadside stop for travelers.

ROY “POPS” CLINE WAS, TO PUT IT MILDLY, AN opportunistic entrepreneur. This assessment comes from his grandson, George Everage, a retired Albuquerque accountant. Everage grew up on stories of the old days, tales recounted by his parents and grandparents, and he vividly recalls them even now. From the 1910s through the 1920s, Cline, his wife, their son, and six daughters moved around, from Oklahoma to Rutherton, near Tierra Amarilla. In Rutherton, Pops ran a post office and a nickel theater in a tent, until the harsh winters convinced them to seek warmer climes further south. He traded the post office for a chicken farm, only to find the “farmhouse” was a dugout. Next, he traded that for a hotel in Buford, a town that would eventually become Moriarty.

The Cline daughters were instrumental to Pops’ early ventures, providing the workforce needed for his growing ambitions. Soon, he had accumulated enough capital to purchase acreage where old Highway 6 intersected with Highway 2. It’s important to remember that “highway” was a generous term in those days. Highway 6 was essentially a dirt road carved across New Mexico. Through Tijeras Canyon, it was barely better than a cattle trail. By 1926, drivers heading west could take the newly paved Route 66 north from Santa Rosa, loop through Santa Fe, and then descend to Albuquerque. However, maps suggested that Highway 6 would be the quicker route, and many travelers opted for it. Pops, ever the opportunist, opened not one, but two service stations – a Standard and a Conoco – strategically placed across from each other to catch travelers coming from either direction.

Whenever the rudimentary bulldozed route shifted, Pops simply relocated his makeshift stations. Then, a stroke of luck: a political decision in Santa Fe resulted in Route 66 being realigned directly through his land. Pops had struck gold. He built a proper white store, proudly displaying his name: Cline’s (with the apostrophe). His 15-cent bowls of chili became legendary, drawing customers from miles around. And, given the state of the roads, he made more profit fixing flat tires than selling gasoline.

From 1938 to 1940, the family weathered some of the most brutal blizzards New Mexico has ever seen. Perched at over 7,000 feet, exposed to the elements with only barbed-wire fences as windbreaks, Clines Corners (now without the apostrophe, as it appeared on maps) has always been at the mercy of Mother Nature. Everage recounts tales and shows photos of snowdrifts so high they threatened to engulf the outhouse. “And when the snow melts,” he adds, “the soil out there is just caliche that turns to clay. Everyone would get stuck.”

Owner George Cook with his son Nicholas, learning the ropes of the family business at Clines Corners Travel Center.

Owner George Cook with his son Nicholas, learning the ropes of the family business at Clines Corners Travel Center.

Eventually, Pops sold Clines Corners to a pair of state policemen and moved his family to Kingman, Arizona, to open a similar venture near the Hoover Dam. Business boomed until World War II began, and resources – gasoline, food, labor – were diverted to the war effort. Pops then relocated the family to Vaughn, New Mexico (“He bounced around,” Everage says of his grandfather’s entrepreneurial spirit), where he ran the Doxie Hotel. Here, he made the most money of his life, selling meals and whiskey to soldiers heading out on troop trains that passed through daily.

In the 1950s, Pops launched Flying Cline Ranch, a competitor to his original Clines Corners, about 19 miles east on Route 66. After a threat of a lawsuit from the new owners of Clines Corners, he changed the name to Flying C. Everage’s father, also named George, had married Mae Lucille, the prettiest of the Cline daughters, and occasionally helped out at Flying C. During the summers, Flying C employed 48 people, served lunch to 22 busloads of tourists daily, and, somewhat less legally, operated five slot machines that conveniently covered all overhead expenses. Young George got a firsthand look at the numerous roadside stops that lined Route 66 in its heyday. “Between Clines Corners and Santa Rosa, there were 25 to 30 of these mom-and-pop places,” he recalls. “One even had a zoo, with animals kept in terrible conditions. One had a bear. Almost every place had a couple of emaciated rattlesnakes.”

By this time, the state policemen who bought Clines Corners had parted ways. One of them opened yet another Route 66 attraction, the Longhorn Ranch, a faux Western town in Moriarty, complete with stagecoach rides, Native American dances, and “a museum with antique firearms and two-headed calves,” according to Everage.

However, as air travel became more accessible and affordable, the era of the classic roadside stop began to fade. The remnants of the Longhorn Ranch sign can still be seen, but little else remains. The rise of interstates and the shift from rail to big-rig freight transportation led to the consolidation of roadside businesses. The few survivors evolved into sprawling truck plazas, now mostly owned by national chains like Love’s, Flying J, and Travel Centers of America.

Clines Corners, remarkably, persevered. It remained locally owned and operated, and crucially, it remained the only business for miles in any direction. Its 40,000 square feet stands as a beacon of human interest and much-needed respite amidst the vast, rolling New Mexico ranchland.

A vibrant display of tchotchkes and food items enticing customers at Clines Corners Travel Center, open 24/7.

A vibrant display of tchotchkes and food items enticing customers at Clines Corners Travel Center, open 24/7.

“THERE’S SOME OLD SAYINGS IN THE BUSINESS,” explains George Cook, the current owner. “One of the most important is ‘Buy the merchandise right.’ That means volume buying. I’m the biggest buyer of souvenir merchandise in New Mexico.”

Besides Clines Corners, Cook owns the Covered Wagon, a sprawling tourist emporium in Albuquerque’s Old Town Plaza. He has also operated the Sundancer Trading Company and Thunderbird Curio shops at the Albuquerque Sunport for 32 years, and manages three businesses near his family’s original homestead: Taos Trading, Taos Cowboy, and Taos Mercantile.

“I used to come out here when I was a kid,” Cook recalls, taking a break in a vinyl booth at Clines Corners’ Subway. “My dad had a jewelry display here. I got to know everyone. I saw the opportunity.”

Today, he owns 1,500 acres in the area, much of it prime frontage along I-40 and US 285, allowing him to pepper the landscape with his Burma Shave-style billboards. “Only advertising I need,” he states confidently. He provides employee housing in a trailer park, accommodating up to 30 families, a significant perk for those who work overnight shifts or find themselves stranded during the occasional severe snowstorms.

Stephanie Urioste, who assists General Manager Anderson with the daily operations of Clines Corners, has experienced her share of these weather-related shutdowns. “If they close the interstate, the workers and travelers who are here, stay here,” she explains. “We open the restaurant, and there are people everywhere, trucks everywhere. It’s chaotic.”

However, Urioste also remembers moments of unexpected kindness. Last year, after a massive snowstorm, one of the stranded travelers, a complete stranger, grabbed a shovel and started digging out car after car. “Sometimes a random person, you just don’t know what they’re going to do,” she marvels.

A curated selection of Native American pottery for sale at Clines Corners Travel Center, New Mexico.

A curated selection of Native American pottery for sale at Clines Corners Travel Center, New Mexico.

A large portion of Clines Corners’ clientele comes from Texas, particularly during the winter months. They head north, stocking up supplies before hitting the ski resorts in Santa Fe, Taos, and Colorado. In the summer, visitors from all corners of the globe fill the aisles. With so many people, it’s easy to miss details, like the colossal buffalo head mounted on a pillar, or the display of bullwhips nearby.

Because at Clines Corners, you truly never know what you might need on the road. Forgot a dog dish? The convenience store has you covered, along with collars, leashes, blue tarps, bungee cords, and even a jack. A $695 amethyst geode sits near vintage lava lamps, close to a display of novelty boxer shorts emblazoned with humorous sayings like “BEWARE OF NATURAL GAS.”

Sheila Foot presides over the fudge counter, a Clines Corners institution that has been satisfying sugar cravings for decades with flavors like the ever-popular pecan praline. “I have a lot of repeat customers,” she says. “One guy comes in every six months and buys two full slabs of lemon meringue pie fudge. I make it just for him. He calls ahead. He comes twice a year from Arizona, because he has property in New York. He buys other things too, of course.”

The candy selection is equally impressive: bulk containers of saltwater taffy, mini Bit-O-Honey bars, Jelly Bellys, Lemonheads, and jawbreakers. T-shirts are the top seller, but the horno-shaped incense burners with cedar, piñon, and juniper scents are a close second. Glass cases at the back display pieces of “Genuine Native Made” Navajo and Zuni jewelry, sourced by Cook from a dealer in Gallup. While mass-produced, the jewelry is attractive and fulfills the tourist desire to return home with something shiny and distinctly Southwestern.

“There is no better business than the tourist trade,” Cook asserts. “People are out to have fun. They want to learn things. You deal with people who are happy.”

Owner George Cook, the driving force behind keeping Clines Corners Travel Center a thriving family business and roadside attraction.

Owner George Cook, the driving force behind keeping Clines Corners Travel Center a thriving family business and roadside attraction.

Indeed, just as skepticism about purchasing a coonskin cap (that doesn’t quite fit) began to wane, a $140 buttery-soft leather apron caught the eye – a perfect birthday gift for a brother. Suddenly, the possibilities expanded: silly trinkets for nieces’ Christmas stockings, a chile-print onesie for an upcoming baby shower, a forgotten birthday card, all available and even mailable from Clines Corners. Phil Collins crooned over the sound system, prompting a moment of reflection: Could this quirky roadside stop actually be… enjoyable? Gas prices aside (Clines Corners sells two million gallons annually, a number poised to increase with the new truck stop), could this be, dare we say, the best place on earth?

And then, reality intruded.

Cook was spotted amidst a group of staff near the candy shop, gesturing emphatically at a section of the ceiling yet to be renovated. Dust, dislodged by the ongoing construction, was filtering down onto the merchandise. “Shut it down,” Cook declared, and it wasn’t the new fire-suppression piping he meant.

He meant the gift shop.

Like a well-drilled team, employees began moving merchandise into storage, T-shirts piled into the candy area (which, along with the convenience store, would remain open), and preparing to cordon off the gift shop, leaving only a hallway accessible from the restrooms to Subway. “For how long?” Sixty days, Cook replied, the words landing like a hammer blow.

It was January’s gray heart. Sixty days meant late March before reopening. For a business that thrived as a way station, a brief stop on a journey, a place where anonymity reigned but personalized pocketknives offered fleeting proof of presence, this closure felt like an existential pause. A line from Waiting for Godot echoed in the mind: “We always find something, eh Didi, to give us the impression we exist?”

Stephanie Urioste expertly prepares a fresh batch of Cline Corners' famous fudge, a long-standing sweet treat for travelers.

Stephanie Urioste expertly prepares a fresh batch of Cline Corners' famous fudge, a long-standing sweet treat for travelers.

Resolved to find meaning in the interim, two boxes of the best fudge were procured. Then, a final encounter with Zoltar, who had been persistently calling out near the restrooms with “Vott are you vaiting for?” A dollar bill was inserted into the slot. Zoltar lurched to life, flapping mannequin arms and speaking in a culturally insensitive accent, the words lost in translation. And then, no fortune card dispensed.

Fate remained unwritten. As the sun dipped below a hazy sky, the drive continued, three billboards flashing in farewell:

CLINES CORNERS / THANK YOU. CLINES CORNERS / COME BACK SOON. CLINES CORNERS / TRAVEL SAFELY.