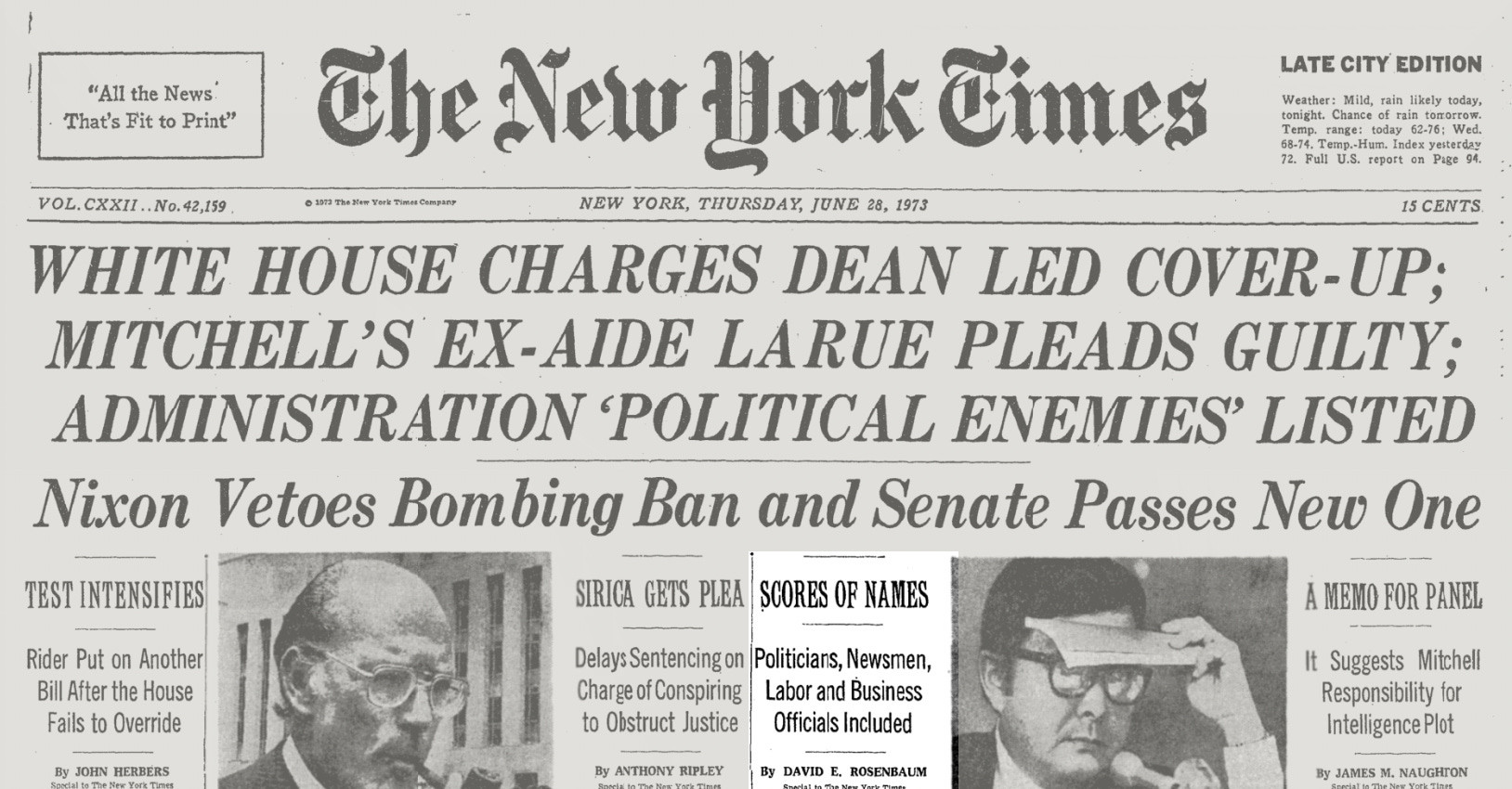

As reported in a New York Times article from June 28, 1973, Nixon’s ban on soybean exports was a story relegated to the lower half of the front page – “below the fold,” as we used to say in the days of printed newspapers. Above it, the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War dominated the headlines. Reading about this now, I was struck by a sudden, whimsical thought: could I have actually held this very edition of the newspaper in my hands as a child? It’s entirely plausible. My parents subscribed to the Times, and my father even worked there. Though I was just shy of eleven and more concerned with baseball stats than political dramas or, heaven forbid, soybean export policies, I vividly recall the Watergate saga as my personal introduction to the world of politics. This reflection sparked an even more curious notion: could this mundane news item, about soybeans no less, somehow function as a Time Travel Machine, whisking me back to that specific period?

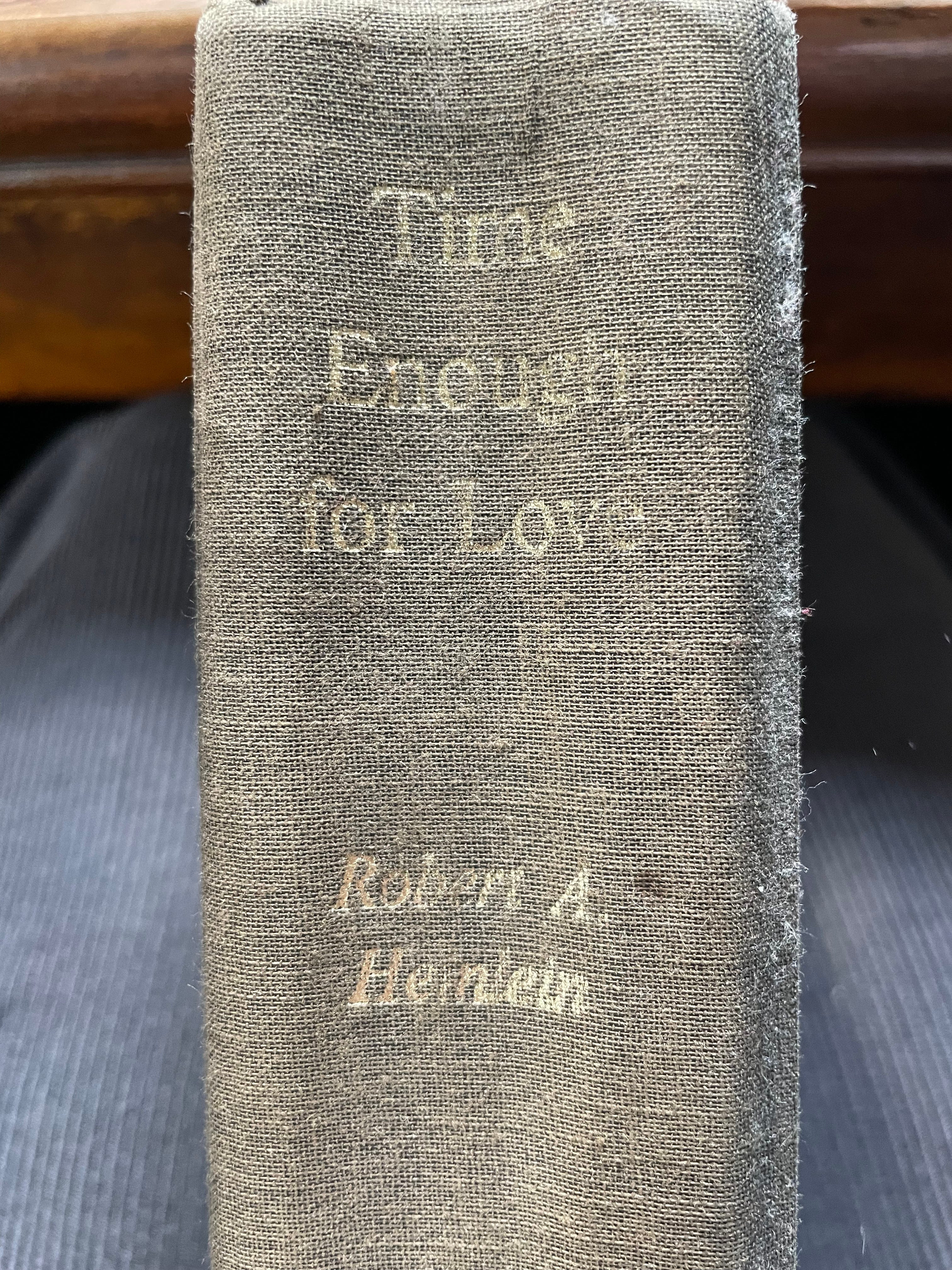

Perhaps my father’s work was featured in that very issue. What could have been occupying his thoughts amidst such significant moments in soybean history? A quick search revealed that in 1973, he was the editor of the Sunday New York Times Book Review. While his bylines were scarce in the daily paper then, I discovered that later that summer, in August, he reviewed two science fiction novels: Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama and Robert Heinlein’s Time Enough For Love.

It’s genuinely amusing to reread his review of Heinlein:

Heinlein. Well, Heinlein is authoritarian; he is sexist; he is Buck Rogers out of Ayn Rand after an unfortunate tryst with Zane Grey; prophet of a Norman O. Browning of America, with Silly‐Putty instead of sex organs—not the fascist some silly people have accused him of being (“There is something rotten at the very heart of German culture,” he says), but a man so smug in his own chromosomes that he would prefer to see the universe in a Heinlein zygote. He is also a damned fine story‐teller; not to read him is to lack curiosity and the capacity to enjoy.

Even as I chuckled at my father’s characteristic prose, a memory surfaced with striking clarity, one that had been dormant for so long. Suddenly, the summer of 1973 felt incredibly present.

I could vividly picture my father in the living room of my mother’s house in Peterborough, New Hampshire. He was seated in a yellow armchair, a cigarette in one hand, pen in the other, Time Enough For Love resting in his lap. I remember my childhood impatience keenly. A voracious science fiction reader, I had devoured Heinlein’s previous work, Stranger In A Strange Land, and was eager to read this new release. But, because of his profession, my father had the first opportunity!

Then, I recall the moment he finished the novel, handing it to me with a knowing grin, fully aware of and amused by my youthful eagerness.

A vintage newspaper clipping from The New York Times, dated June 28, 1973, detailing Nixon’s soybean export ban, a seemingly minor event overshadowed by Watergate and Vietnam War headlines.

I still possess that very copy of Time Enough For Love, complete with my father’s dog-eared pages and his cryptic notes scribbled in the margins. This book, more than just a science fiction novel, is a tangible link to that specific moment in time.

There’s a bittersweet layer to this memory. Just a year and a half later, my parents separated. By 1976, my mother, sister, and I had relocated from New York to Gainesville, Florida. For the rest of my life, home was always geographically distant from my father. He passed away in 2008. Last Sunday would have marked his 85th birthday.

Yet, I feel a profound sense of joy in reconnecting with the memory of him in that armchair, crafting his Heinlein review. And I’m somewhat in awe that soybeans, of all things, led me back there, though perhaps I shouldn’t be entirely surprised. If, as I believe, the soybean is indeed ubiquitous and influential, then it is also, in a way, a personal time travel machine, capable of transporting us back through memory.

A well-loved paperback copy of Robert Heinlein’s “Time Enough For Love,” a physical object that serves as a personal time capsule to the author’s memories of his father.

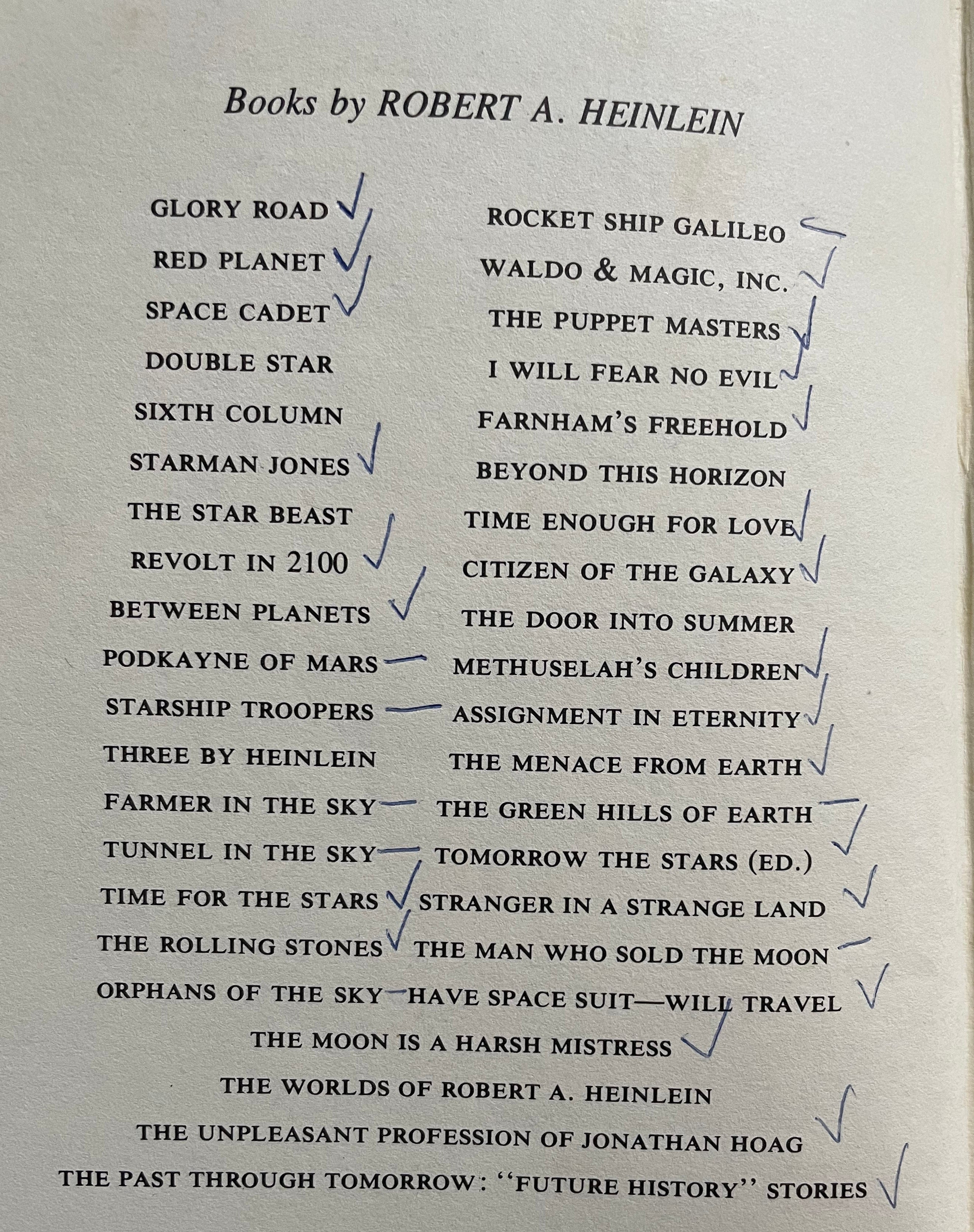

One final detail: the frontispiece of my copy of Time Enough For Love lists all of Heinlein’s books published before 1973, complete with my childhood annotations. I can’t pinpoint when I made these markings. It seems improbable, though not impossible, that I had read two dozen Heinlein novels by the age of eleven. Nor can I decipher the distinction between a “dash” and a “check” mark, as I’m certain I read all books marked with either.

What is clear is that, while my opinion of Heinlein’s work has diminished over the past half-century, I now feel a slight pang of regret that I never fully completed reading everything on that list. Perhaps, in the end, I simply didn’t have time enough for Heinlein.

The inside cover of “Time Enough For Love” with a list of Heinlein’s works, annotated by the author in childhood, representing a journey through time and literary discovery.